November 15, 2025

It was shortly after midnight on November 1 when Daniel arrived in Montego Bay after eight months working on a farm in Niagara-on-the-Lake. When the taxi headlights illuminated the apocalyptic scene, he was in disbelief. There was only a pile of rubble and twisted beams where his home had been. He had not been able to make contact with his family since Hurricane Melissa slammed into the island four days earlier. He dragged his luggage through debris in the pitchblack streets with only a headlamp to guide him. How would he ever find his family?

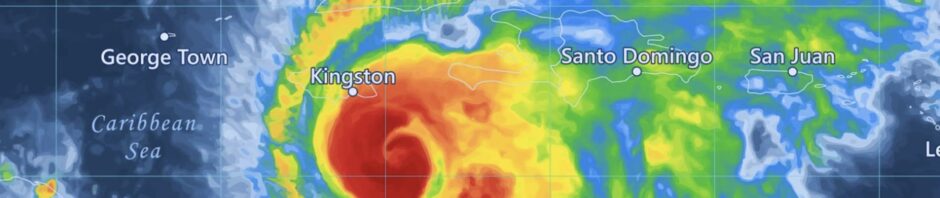

Screenshot

Tuesday, October 28, 2025 marks the most extreme weather disaster in Jamaican history. For three days prior, Hurricane Melissa had intensified into a category 5 hurricane off of the coastal waters of the island. By the time it slammed into the western parishes, the sustained winds of 295 km per hour defied the imagination. Melissa was the strongest recorded hurricane to make landfall on the island, surpassing that of Hurricane Gilbert in 1988.

Roughly half of the farm workers in Niagara come from the parishes of Westmoreland and St. Elizabeth, which experienced almost total destruction. Record rainfall – as much as 30 inches in some areas – and the accompanying storm surge wiped out coastal communities and destroyed roads, making rescue impossible in the days that followed. It is estimated that 70-80% of all structures lost their roof or collapsed entirely in those two parishes alone. Schools are completely destroyed with many others across the island unable to open due to structural damage. Historic churches that survived hurricanes for the past 200 years are left with only one or two walls standing.

Close to 100 Jamaican men were still working on farms and greenhouses in Niagara-on-the-Lake when the hurricane hit. They had already suffered through sleepless nights worrying about the safety of their families, farms, and homes. Every spare minute was spent connecting with loved ones and giving final instructions to family members who would have to shoulder the responsibilities of trying to secure their houses.

On the morning of Tuesday, October 28, all communication came to an abrupt halt. Waiting to hear from loved ones became a special kind of agony, fearing the worst as the hurricane continued to break previous records. This hurricane represented the first ever triple threat of not only wind and water, but the unusual length of time that it stalled over the western half of the island.

Close to 20 men were scheduled to fly home the first week of November after the completion of their eight month contract. With their bunkhouses cleaned and fridges emptied, they were then informed that the airports were closed. Now they waited and worried, trying not to panic as they watched the news unfold so far from home.

After hearing the news of the impending storm, we immediately began purchasing rechargeable headlamps to distribute to the remaining men before they returned. It was important to let our Jamaican neighbours know that they were not forgotten.

The mood was sombre at the first farm we visited the day after the hurricane hit, where men were waiting anxiously for flight information. Scrolling endlessly on their phones they hoped to catch a glimpse of their communities on the latest news updates. Only one or two men had been able to make contact with a family member, learning that they had lost everything. Farms and crops that they relied on during the winter months were wiped out.

Several days after the hurricane, flight plans kept changing when it was determined that Sangster Airport in Montego Bay would be unable to open due to the extensive damage. News reports revealed that most of the roads on the western half of the island were impassable, many washed out entirely. Finally they received word at the farm that the rescheduled flights were also being rerouted to Kingston. Men like Daniel who lived close to Montego Bay now had to find a way to travel back the entire length of the island.

Returning farm workers found themselves navigating through crowds at Kingston Airport which had to handle the air traffic for both airports as well as cargo planes loaded with relief supplies. It was almost impossible for Daniel to find a way home amidst the chaos. Finally he and a coworker found a taxi that was willing to take the substantial risk of a 179 km journey for almost $500 CDN. They left Kingston shortly after noon. The farther west they travelled, the more horrifying the devastation became. Homes decimated, trees like toothpicks strewn every which way, stripped of leaves and bark.

In the falling dark it felt like a nightmare that wouldn’t end, the car headlights illuminating a path as they navigated washed out roads, downed hydro poles, live wires, trees and debris.

A drive that would normally take 3 ½ hours, now took almost 12 hours. Arriving in Montego Bay he was not prepared for the devastation looming through the darkened streets. When he finally arrived at his address the taxi dropped him off in front of a pile of rubble and twisted beams. Dragging his luggage with only a headlamp to guide him through the now unfamiliar streets he hoped to find shelter in his church nearby. Only one wall remained, everything shattered. He wandered through the apocalyptic setting until he finally found the house of a friend.

He was unable to rest until he found his family in a shelter later the next day. Finally reunited, they have remained in the shelter with nowhere to go. His story has become a familiar one as we continue to hear from those who have returned home to the areas most affected.

It has become a familiar refrain to hear “I thank God for life” when I ask about their loved ones. One man’s wife relayed to him that their house literally exploded while she and their children were seeking shelter in their “hurricane proof” room. They were forced to flee to a neighbour’s house at the height of the storm, an incredibly dangerous risk because of the flying debris. Then the roof lifted off piece by piece on the neighbour’s house and they all had to flee to a third house which remained relatively intact for the remainder of the storm.

A beautiful farm with mature fruit trees, flower borders and hundreds of sweet peppers all washed away.

The aftermath of a meticulous market garden.

Severe flooding has hampered rescue operations, resulting in many rural communities unable to access aid or necessities provided by humanitarian agencies. It may be February before some communities have electricity restored.

Some families have generators, but it costs over $50 CDN for the gas to run it for only five hours. The destruction from Hurricane Beryl last year left many communities without hydro for over three months, so for many the cost of the gas over that length of time is prohibitive.

Thousands have been left homeless, including some of our friends from local farms. Many of those I have talked to are extremely concerned about the threat of cholera and mosquito-born viruses such as dengue fever and zika in the flooded areas.

Two and a half weeks after Hurricane Melissa tore into the island, I am beginning to hear from some families of farm workers. One woman who lives not too far from the famous Appleton Estate in St. Elizabeth sent me an audio message this week, her voice cracking from a dry throat and lack of safe drinking water. They have no electricity, no internet, except for that brief moment of connection.She closed her message with this thought, “It’s very, very rough but God still smiles at the stars.”

A little light in this time of darkness can provide enough illumination to each of us, to help each other find our way forward, one step at a time.